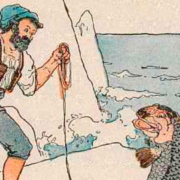

The tale of “The Fisherman and his Wife” tells a story for our times: Our human willfulness can finally ask too much of Mother Nature. In “Frau Holle,” discussed in last month’s article, we saw that cooperating with Mother Nature brought golden rewards. Attempting to manipulate Mother Nature likewise got results: but tar, rather than gold. “The Fisherman and his Wife” depict Mother Nature becoming more and more agitated by human demands.

As I wrote in last month’s article, we can read some of these traditional stories literally. Other traditional stories don’t make any sense at all from a literal point of view. After a certain point in the narrative we have to move to allegory and symbol. First, what do I mean by “allegory” and “symbol”?

I mean a story (or poem or picture, etc.) in which the characters and events express or reveal a pattern that informs/structures the narrative of different characters in different circumstances. Usually an allegory represents particular moral, ethical, religious, or political ideas. And I would add: psychological insights.

A symbol, 1) means more than it (literally) is, and 2) seems to convey endless meanings. We can legitimately understand a symbol in many ways. An authentic symbol continues to fascinate us. If only we had more words, we could better say what it means.

So when you read “The Fisherman and his Wife,” let yourself “hear” the tale on many levels.

There was once a fisherman who lived with his wife in a pigsty, close by the seaside. The fisherman used to go out all day long a-fishing; and one day, as he sat on the shore with his rod, looking at the sparkling waves and watching his line, all of a sudden his float was dragged away deep into the water: and in drawing it up he pulled out a great fish. But the fish said, ’Pray let me live! I am not a real fish; I am an enchanted prince: put me in the water again, and let me go!’ ’Oh, ho!’ said the man, ’you need not make so many words about the matter; I will have nothing to do with a fish that can talk: so swim away, sir, as soon as you please!’ Then he put him back into the water, and the fish darted straight down to the bottom, and left a long streak of blood behind him on the wave.

When the fisherman went home to his wife in the pigsty, he told her how he had caught a great fish, and how it had told him it was an enchanted prince, and how, on hearing it speak, he had let it go again. ’Did not you ask it for anything?’ said the wife, ’we live very wretchedly here, in this nasty dirty pigsty; do go back and tell the fish we want a snug little cottage.’

The fisherman did not much like the business: however, he went to the seashore; and when he came back there the water looked all yellow and green. And he stood at the water’s edge, and said:

’O man of the sea!

Hearken to me!

My wife Ilsebill

Will have her own will,

And hath sent me to beg a boon of thee!’

Then the fish came swimming to him, and said, ’Well, what is her will? What does your wife want?’ ’Ah!’ said the fisherman, ’she says that when I had caught you, I ought to have asked you for something before I let you go; she does not like living any longer in the pigsty, and wants a snug little cottage.’ ’Go home, then,’ said the fish; ’she is in the cottage already!’ So the man went home, and saw his wife standing at the door of a nice trim little cottage. ’Come in, come in!’ said she; ’is not this much better than the filthy pigsty we had?’ And there was a parlour, and a bedchamber, and a kitchen; and behind the cottage there was a little garden, planted with all sorts of flowers and fruits; and there was a courtyard behind, full of ducks and chickens. ’Ah!’ said the fisherman, ’how happily we shall live now!’ ’We will try to do so, at least,’ said his wife.

Everything went right for a week or two, and then Dame Ilsebill said, ’Husband, there is not near room enough for us in this cottage; the courtyard and the garden are a great deal too small; I should like to have a large stone castle to live in: go to the fish again and tell him to give us a castle.’ ’Wife,’ said the fisherman, ’I don’t like to go to him again, for perhaps he will be angry; we ought to be easy with this pretty cottage to live in.’ ’Nonsense!’ said the wife; ’he will do it very willingly, I know; go along and try!’

The fisherman went, but his heart was very heavy: and when he came to the sea, it looked blue and gloomy, though it was very calm; and he went close to the edge of the waves, and said:

’O man of the sea!

Hearken to me!

My wife Ilsebill

Will have her own will,

And hath sent me to beg a boon of thee!’

’Well, what does she want now?’ said the fish. ’Ah!’ said the man, dolefully; ’my wife wants to live in a stone castle.’ ’Go home, then,’ said the fish; ’she is standing at the gate of it already.’ So away went the fisherman, and found his wife standing before the gate of a great castle. ’See,’ said she, ’is not this grand?’ With that they went into the castle together, and found a great many servants there, and the rooms all richly furnished, and full of golden chairs and tables; and behind the castle was a garden, and around it was a park half a mile long, full of sheep, and goats, and hares, and deer; and in the courtyard were stables and cow-houses. ’Well,’ said the man, ’now we will live cheerful and happy in this beautiful castle for the rest of our lives.’ ’Perhaps we may,’ said the wife; ’but let us sleep upon it, before we make up our minds to that.’ So they went to bed.

The next morning when Dame Ilsebill awoke it was broad daylight, and she jogged the fisherman with her elbow, and said, ’Get up, husband, and bestir yourself, for we must be king of all the land.’ ’Wife, wife,’ said the man, ’why should we wish to be the king? I will not be king.’ ’Then I will,’ said she. ’But, wife,’ said the fisherman, ’how can you be king–the fish cannot make you a king?’ ’Husband,’ said she, ’say no more about it, but go and try! I will be king.’ So the man went away quite sorrowful to think that his wife should want to be king. This time the sea looked a dark grey colour, and was overspread with curling waves and the ridges of foam as he cried out:

’O man of the sea!

Hearken to me!

My wife Ilsebill

Will have her own will,

And hath sent me to beg a boon of thee!’

’Well, what would she have now?’ said the fish. ’Alas!’ said the poor man, ’my wife wants to be king.’ ’Go home,’ said the fish; ’she is king already.’

Then the fisherman went home; and as he came close to the palace he saw a troop of soldiers, and heard the sound of drums and trumpets. And when he went in he saw his wife sitting on a throne of gold and diamonds, with a golden crown upon her head; and on each side of her stood six fair maidens, each a head taller than the other. ’Well, wife,’ said the fisherman, ’are you king?’ ’Yes,’ said she, ’I am king.’ And when he had looked at her for a long time, he said, ’Ah, wife! What a fine thing it is to be king! Now we shall never have anything more to wish for as long as we live.’ ’I don’t know how that may be,’ said she; ’never is a long time. I am king, it is true; but I begin to be tired of that, and I think I should like to be emperor.’ ’Alas, wife! Why should you wish to be emperor?’ asked the fisherman. ’Husband,’ said she, ’go to the fish! I say I will be emperor.’ ’Ah, wife!’ replied the fisherman, ’the fish cannot make an emperor, I am sure, and I should not like to ask him for such a thing.’ ’I am king,’ said Ilsebill, ’and you are my slave; so go at once!’

So the fisherman was forced to go; and he muttered as he went along, ’This will come to no good, it is too much to ask; the fish will be tired at last, and then we shall be sorry for what we have done.’ He soon came to the seashore; and the water was quite black and muddy, and a mighty whirlwind blew over the waves and rolled them about, but he went as near as he could to the water’s brink, and said:

’O man of the sea!

Hearken to me!

My wife Ilsebill

Will have her own will,

And hath sent me to beg a boon of thee!’

’What would she have now?’ said the fish. ’Ah!’ said the fisherman, ’she wants to be emperor.’ ’Go home,’ said the fish; ’she is emperor already.’

So he went home again; and as he came near he saw his wife Ilsebill sitting on a very lofty throne made of solid gold, with a great crown on her head full two yards high; and on each side of her stood her guards and attendants in a row, each one smaller than the other, from the tallest giant down to a little dwarf no bigger than my finger. And before her stood princes, and dukes, and earls: and the fisherman went up to her and said, ’Wife, are you emperor?’ ’Yes,’ said she, ’I am emperor.’ ’Ah!’ said the man, as he gazed upon her, ’what a fine thing it is to be emperor!’ ’Husband,’ said she, ’why should we stop at being emperor? I will be pope next.’ ’O wife, wife!’ said he, ’how can you be pope? There is but one pope at a time in Christendom.’ ’Husband,’ said she, ’I will be pope this very day.’ ’But,’ replied the husband, ’the fish cannot make you pope.’ ’What nonsense!’ said she; ’if he can make an emperor, he can make a pope: go and try him.’

So the fisherman went. But when he came to the shore the wind was raging and the sea was tossed up and down in boiling waves, and the ships were in trouble and rolled fearfully upon the tops of the billows. In the middle of the heavens, there was a little piece of blue sky, but towards the south, all was red as if a dreadful storm was rising. At this sight, the fisherman was dreadfully frightened, and he trembled so that his knees knocked together: but still he went down near to the shore, and said:

’O man of the sea!

Hearken to me!

My wife Ilsebill

Will have her own will,

And hath sent me to beg a boon of thee!’

’What does she want now?’ said the fish. ’Ah!’ said the fisherman, ’my wife wants to be pope.’ ’Go home,’ said the fish; ’she is pope already.’

Then the fisherman went home and found Ilsebill sitting on a throne that was two miles high. And she had three great crowns on her head, and around her stood all the pomp and power of the Church. And on each side of her were two rows of burning lights, of all sizes, the greatest as large as the highest and biggest tower in the world, and the least no larger than a small rushlight. ’Wife,’ said the fisherman, as he looked at all this greatness, ’are you pope?’ ’Yes,’ said she, ’I am pope.’ ’Well, wife,’ replied he, ’it is a grand thing to be pope; and now you must be easy, for you can be nothing greater.’ ’I will think about that,’ said the wife. Then they went to bed: but Dame Ilsebill could not sleep all night for thinking what she should be next. At last, as she was dropping asleep, morning broke, and the sun rose. ’Ha!’ thought she, as she woke up and looked at it through the window, ’after all I cannot prevent the sun rising.’ At this thought, she was very angry, and wakened her husband, and said, ’Husband, go to the fish and tell him I must be lord of the sun and moon.’ The fisherman was half asleep, but the thought frightened him so much that he started and fell out of bed. ’Alas, wife!’ said he, ’cannot you be easy with being pope?’ ’No,’ said she, ’I am very uneasy as long as the sun and moon rise without my leave. Go to the fish at once!’

Then the man went shivering with fear; and as he was going down to the shore a dreadful storm arose so that the trees and the very rocks shook. And all the heavens became black with stormy clouds, and the lightning played, and the thunder rolled; and you might have seen in the sea great black waves, swelling up like mountains with crowns of white foam upon their heads. And the fisherman crept towards the sea, and cried out, as well as he could:

’O man of the sea!

Hearken to me!

My wife Ilsebill

Will have her own will,

And hath sent me to beg a boon of thee!’

’What does she want now?’ said the fish. ’Ah!’ said he, ’she wants to be lord of the sun and moon.’ ’Go home,’ said the fish, ’to your pigsty again.’

And there they live to this very day.

At one level of reading this tale needs no interpretation. Even though I have read it many times and thought about it often, the figure of Dame Ilsebill, her intimidated fisherman husband, the enchanted prince / fish, and the progressively more agitated ocean arouse an instinctive gut-level fear in me. The Greek word hubris characterizes Dame Ilsebill’s attitude and behavior. “Hubris . . . describes a personality quality of extreme or foolish pride or dangerous overconfidence, often in combination with (or synonymous with) arrogance. In its ancient Greek context, it typically describes behavior that defies the norms of behavior or challenges the gods, and which in turn brings about the downfall, or nemesis, of the perpetrator of hubris.”

Enough said?

Without going into details about each of the figures, we understand the message of the tale: For months now, the news has reported the fall of prominent men who have exploited their social, professional and/or political positions for personal gratification. But can we get more out of this story than meets the eye? In this story we want to understand more what the fisherman, his wife, the fish (who is an enchanted prince) and the ocean may mean. We can deepen our understanding as with a dream that makes an emotional and intuitive impact. This moves us into the allegorical and symbolic dimension. I’ll start with the ocean.

Myths and stories from the past give us a clue to the meaning people have experienced in various natural phenomena. We recall that creation according to the Book of Genesis commences when God separates the waters above from the waters below. The Babylonian account predates even the Biblical account:

When skies above were not yet named

Nor earth below pronounced by name,

Apsu, the first one, their begetter

And maker Tiamat, who bore them all,

Had mixed their waters together,

But had not formed pastures, nor discovered reed-beds;

When yet no gods were manifest,

Nor names pronounced, nor destinies decreed,

Then gods were born within them.

Another set of creation myths feature a creature that dives deep into the primal ocean to find bits of sand or earth out of which the solid land is formed.

The earth-diver is a common character in various traditional creation myths. In these stories a supreme being usually sends an animal into the primal waters to find bits of sand or mud with which to build habitable land. . . . Earth-diver myths are common in Native American folklore but can be found among the Chukchi and Yukaghir, the Tatars and many Finno-Ugrian traditions. . . .

Characteristic of many Native American myths, earth-diver creation stories begin as beings and potential forms linger asleep or suspended in the primordial realm. The earth-diver is among the first of them to awaken and lay the necessary groundwork by building suitable lands where the coming creation will be able to live. In many cases, these stories will describe a series of failed attempts to make land before the solution is found.

Following the pattern of these creation stories, the ocean in The Fisherman and his Wife contains all possibilities, not just for life, but for life on dry land, which is where we humans live. Viewed psychologically, the ocean symbolizes everything of which we are consciously aware and the source of everything. The shorthand for this is “the unconscious:” everything that exists but of which I am not now, and perhaps never yet was, conscious, but nevertheless “something” real, powerful, some potential or “energy.” I want to call this “the matrix of being,” the source and continuing ground of our existence.

The human figures of the fisherman and his wife form an ambivalent pair. We must not get hung up on the gender of the figures. Rather they correspond to a capacity to take action and make choices and decisions (the fisherman), and the innate human function of desire (the wife). If we must personalize the figures, then the fisherman could be a flesh-and-blood man, and the wife would then be that man’s desire nature. (As I suggested earlier, from this point-of-view the fisherman and his wife characterize many men who have fallen because they have abused their powerful positions for financial, professional, and/or sexual gratification.) Turn this around, and the pattern can just as accurately describe a flesh-and-blood woman who lets her desire nature compromise her ability to make appropriate choices and decisions. In either case we see hubris as the outcome: over-weening ambition or greed or lust for power leads to downfall.

Back to the story.

The human capacity for judgment (the fisherman) encounters something bigger than (human) life: a powerful content from the matrix of being (the fish, which is actually a prince under a spell). The human desire nature (the wife) overpowers the capacity for judgment (the fisherman), who then exploits a powerful content from the matrix of being (the fish), with the consequence that the matrix of being (the ocean) becomes more and more agitated.

I need to introduce one more term into the discussion of this tale: inflation. We have various colloquial terms that vividly depict inflation: too big for his britches; all puffed up; pompous; high-and mighty. All of these terms, and others, identify a state exceeding the human dimension. I might add, as a paraphrase of hubris; the phrase, “pride commeth before the fall.”

In the tale, the human capacity for judgment (the fisherman) becomes inflated by the prospect of profiting (new cottage, castle, etc.) from the matrix of being (the ocean). With each demand, the fisherman (the capacity for judgment) initially hesitates, then, after getting what was demanded, the fisherman believes the wife (the desire nature) will be satisfied. He has an anxious little conversation with himself: Surely we’ll live happily ever after. But Dame Ilsebill, “We’ll see.”

For some reason I am reminded of what J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project, said as he witnessed the first above-ground atomic explosion in the desert of New Mexico: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The fisherman goes to the ocean every day to fish. We all do that: the intuition, the insight, the hunch, the surprising discovery, the bright idea. We seek human-scale fish that feed us. But what if we hook the enchanted prince? That could be the get-rich scheme, the “killer app” that will make us rich and famous, the “angle” by which we gain power and prestige, the “ultimate truth” that everybody “must” embrace? Then we have usurped the power of the enchanted prince who is powerless to stop us.

So who is the prince? And what has enchanted him or put him under the spell in the ocean / matrix of being / the unconscious?

Although there have been exceptions, over the last several thousand years a male has been the dominant figure laying out the laws in most social groups. In other words, the human capacity for taking initiative, making judgments and decisions has been imaged as male whereas the human capacity for containing, birthing, nurturing, desiring has been imaged as female. In many societies, these two capacities have become “personalized,” that is attached to anatomical males and female, as in our tale of the fisherman and his wife. Hence our human history of kings, emperors, strong men, dictators, and imperial presidents, and the dynasties they sire.

In our tale, the enchanted prince stands next in line to be king—but not yet. The figure in line to rule, to articulate the way the society is to function, can be dominated by human desire. Shifting from viewing the pattern organization of society to organization of the human psyche, we see that human desire and an inflated although anxious consciousness can usurp that power of the matrix of being to satisfy its own boundless desires.

From time to time each of us faces the temptation to get high and mighty, bigger than our britches, to yield to the temptation to “have it all out” with someone, to “lay down the law,” to “fix it once and for all.” It’s a rush of power – Intoxicating, Self-righteous, Dangerous, Hubris. We don’t have to look far around us to see it doing its mischief in the world today. That’s the easy part. Seeing it operating in ourselves challenges our honesty.

Most of the people I see for psychotherapy and analysis have suffered under one or another form of tyranny: parents, siblings, spouses, employers. Most of them survive on a catch of very little fishes. The temptation, however, sometimes—maybe often—arises in the fantasy of catching the “big fish:” the prospect of setting things right once and for all, of telling it like it is, of finally giving as good as they have gotten. In the long run nothing good comes from acting when in the grip of a bigger-than–human power. We call that “archetypal inflation,” being in the grip of a transpersonal power, a “god.” Legitimate power does acts decisively, soberly, from a position of integrity, and calm inner strength. No drama. No fireworks. No uproar.

As a friend of mine so simply puts it to his clients: Discover who you are. Be who you are. Tell others who you are. Then forget who you are and just be.

That’s the great challenge to us human beings.

1. Originally recorded in the 19th Century by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in their Kinder- und Hausmaerchen. http://www.authorama.com/grimms-fairy-tales-10.html

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubris.Originally recorded in the 19th Century by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in their Kinder- und Hausmaerchen.

3. Genesis 1:2

4. https://www.creationmyths.org/enumaelish-babylonian-creation/

5. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creation_myth#Earth-diver

6. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lb13ynu3Iac