Fifteen years ago, my late friend and colleague, Robert Moore, published a little book whose relevance has lost nothing in the intervening years. In his preface to Facing the Dragon: Confronting Personal and Spiritual Grandiosity, Moore (2003, xi) quotes a sobering passage from Jung’s Answer to Job:

Everything now depends on man: immense power of destruction is given into his hand, and the question is whether he can resist the will to use it, and can temper his will with the spirit of love and wisdom. He will hardly be capable of doing so on his own unaided resources. He needs the help of an “advocate” . . . . The only thing that really matters now is whether man can climb up to a higher moral level, to a higher plane of consciousness, in order to be equal to the superhuman powers which the fallen angels have played into his hands. (1)

Moore shows how “pathological narcissism results from archetypal energies that are not contained and channeled through resources such as spiritual disciplines, ritual practice, utilization of the mythic imagination, and Jungian analysis” (2003, xii). We need not look far to find people inflated with super-human, archetypal energies that generate pathological narcissism and the fantasies that their ICBM is bigger than your ICBM. But we really don’t have to look toward Pong Yang or Moscow or Washington at all: when we’re so sure we are right, a glance in the mirror may reveal another person swelling up with spiritual grandiosity.

“Why,” Moore asks, “do I emphasize the dynamics of human evil in my research and teaching in psychology and spirituality?” (2003, 1) He answers that we must avoid two traps when we face the threat of personal and collective destructiveness. First, a “flight into the light” enables denial and requires very little reflection or action. It’s an easy out. Second, we have to master the temptation to blame our plight on a scapegoat: the one percent; the other party in power; the other gender; immigrants; the poor. All [of us] must respond to the challenge of coming to an understanding of evil that is neither naïve nor grounded in scapegoating of the other, but which may account for some of the forces of destructiveness that threaten to destroy us” (2003, 2).

Lest this sounds abstract or esoteric, I will illustrate with two personal examples, one from my teen years and one from present time. Both reveal my vulnerability to destructive power.

As a sixteen-year-old, I got my driver’s license and a .22 caliber rifle. My grandparents lived on a farm three miles out-of-town. My grandfather was still working at a lumber company, and came home for lunch each day. There were many barn cats. My grandmother believed there were too many. She asked me if I could dispose of some of them. One summer day while my grandfather was at work I went to the farm with my gun and killed several cats. When my grandfather came home, he didn’t say anything – he typically didn’t say much – but I’m sure he noticed that there were fewer cats.

I still feel shame as I tell this story, decades later. That experience vividly showed me how easily I could get intoxicated with and swept away by destructive power.

Fast forward to present time. The lure of exercising destructive power still tempts me. I regularly watch the PBS Newshour, hardly a program given to inciting violent emotions, yet some news stories trigger murderous anger in me. “Shoot the bastards!” Fortunately, the “bastards” are far away and I have no firearm. I am aware that my irritability quickly escalates toward violent fantasies. And it’s not only the news that inflames my anger.

In both examples from my life, an energy gets activated in me that claims power over life and death. In Jungian language, we call this condition “inflation.” From the Christian Bible we have the admonition that “Vengeance is mine, sayeth the Lord.” (2) From ancient Greece, we get the term “hubris,” which is Greek for “too big for his britches.”

One example is King Midas who, in his greed for gold, got his wish. Everything he touched turned to gold. At first, he was delighted: roses, apples, etc., turned into gold. But whatever he touched – including what touched his lips – turned to gold. Realizing he was doomed to die of hunger and thirst, Midas begged to be freed from his golden touch.

Moore references spiritual disciplines, ritual practice, utilization of the mythic imagination, and Jungian analysis as approaches to these energies that inflate us beyond our human proportions. A story from Greek mythology illustrates hubris in action. Apollo, the Sun God, fathered a son with a human woman. The boy, Phaeton, wanted proof that Apollo was his father. Apollo promised to grant whatever Phaeton asked for. “I want to drive your sun chariot for a day.” Apollo hadn’t thought ahead. “I can’t let you do that. Even I have a hard time controlling the horses. Even I am afraid some times.” But to no avail. Not able to withdraw his (Apollo’s) promise, Phaeton takes off in the sun chariot.

The boy has already taken possession of the fleet chariot, and stands proudly, and joyfully, takes the light reins in his hands, and thanks his unwilling father. Meanwhile, the sun’s swift horses, Pyroïs, Eoüs, Aethon, and the fourth, Phlegon, fill the air with fiery whinnying and strike the bars with their hooves. When Tethys, ignorant of her grandson’s fate, pushed back the gate, and gave them access to the wide heavens, rushing out, they tore through the mists with their hooves and, lifted by their wings, overtook the East winds rising from the same region. But the weight was lighter than the horses of the Sun could feel, and the yoke was free of its accustomed load. Just as curved-sided boats rock in the waves without their proper ballast, and being too light are unstable at sea, so the chariot, free of its usual burden, leaps in the air and rushes into the heights as though it were empty.

As soon as they feel this, the team of four run wild and leave the beaten track, no longer running in their pre-ordained course. Phaeton was terrified, unable to handle the reins entrusted to him, not knowing where the track was, nor, if he had known, how to control the team. Then for the first time the chill stars of the Great and Little Bears, grew hot, and tried in vain to douse themselves in forbidden waters. And the Dragon, Draco, that is nearest to the frozen pole, never formidable before and sluggish with the cold, now glowed with heat, and took to seething with new fury. . . . .

When the unlucky Phaeton looked down from the heights of the sky at the earth far, far below he grew pale and his knees quaked with sudden fear, and his eyes were robbed of shadow by the excess light. Now he would rather he had never touched his father’s horses, and regrets knowing his true parentage and possessing what he asked for.(3)

The chariot rises too high and melts the polar ice; it swoops too low and dries up the rivers. Heaven and earth complain. Phaeton cannot control the power he has unleashed. To put an end to the destruction, Zeus throws a thunder bold, striking Phaeton, who plunges into the sea.(4)

Hubris, spiritual grandiosity, pathological narcissism, characterizes much of the emotional atmosphere of our times, as cartoons, posters, and TV shows attest. I say “atmosphere” because the energy – the emotion – that empowers hubris infects us all just as polluted air does, but rather than smelling it with our noses we sense it working in our feelings and fantasies.

The Bible, Greek mythology, and contemporary cartoons(note: Hubris comics created by Greg Cravens , header) advise us that a greater power exists. What does Jungian psychology offer us?

Jungian psychology does, of course, cite the stories from the past in which overweening pride, archetypal inflation, spiritual grandiosity, and pathological narcissism depict the consequences. Waking fantasies and dreams from the night can and do offer images that may counterbalance the attitudes and preoccupations of the conscious minds. Psyche, through dreams and fantasies, presents a challenge: pay attention, notice! Sometimes psyche sends urgent messages; sometimes the information comes in subtle ways on the fringes of our waking awareness, or as a mild sense of discomfort or dis-ease, a sensation that “something” isn’t quite in order.

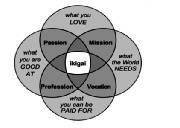

When I notice, I need to take the next step by finding where the image or fantasy has similarities with known stories, movies, myths, or passages from spiritual scriptures. That provides me with the human context, situating the image or fantasy from psyche within the body of experience of the ages. Then I ask: What does that mean for me? What am I doing to which the image or fantasy speaks? Finally, I have to evaluate what I am doing and the compensatory message that psyche offers. These four steps constitute part of a feed-back loop that starts with my action or attitude, psyche’s compensatory comment/response (in the form of a dream, an image, a fantasy), and my understanding and evaluating both my situation and the compensatory information. Here, in brief, we have the outline of a psychological discipline that will satisfy what Moore calls for.

The dangers of personal and spiritual grandiosity appear to be part of being human. Thousands of years of human experience attest the danger of succumbing, whether as King Midas or Phaeton or a contemporary man or woman, you or me. We live in a dangerous, infections emotional atmosphere these days. Sniff the air. Pay attention. Find an advocate to help you work at what’s necessary to climb to a higher moral level and plane of consciousness.

(1) Moore, R. L. (2003). Facing the Dragon: Confronting Personal and Spiritual Grandiosity. Wilmette, IL: Chiron Publications, quoting C.G. Jung (1952/1958), Answer to Job, The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, vol. 11, p. 459. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

“Dr. Robert Moore was Distinguished Service Professor of Psychology, Psychoanalysis and Spirituality in the Graduate Center of the Chicago Theological Seminary where he was the Founding Director of the new Institute for Advanced Studies in Spirituality and Wellness. An internationally recognized psychoanalyst and consultant in private practice in Chicago, he served as a Training Analyst at the C.G. Jung Institute of Chicago and was Director of Research for the Institute for Integrative Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy and the Chicago Center for Integrative Psychotherapy. Author and editor of numerous books in psychology and spirituality, he lectured internationally on his formulation of a neo-Jungian psychoanalysis and integrative psychotherapy. His publications include THE ARCHETYPE OF INITIATION: Sacred Space, Ritual Process and Personal Transformation; THE MAGICIAN AND THE ANALYST: The Archetype of the Magus in Occult Spirituality and Jungian Psychology, and FACING THE DRAGON: Confronting Personal and Spiritual Grandiosity.” (Moore bio by Benjamin Law, blaw@jungchicago,.org). Several MP-3 recordings of Robert Moore’s classes are available from the C.G. Jung Institute (www.jungchicago.org/store).

(2) Romans 12:17-19; Deuteronomy 32:35

(3) Ovid. Metamorphoses, Book II, 150-178, mythological index and illustrations by Hendrik Glotzius. https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/Metamorph2.php#anchor_Toc64106105

(4) Ibid, lines 272-328

(5). http://hubriscomics.com/comic/hubris-they-still-have-paper/. Hubris Comics, created by Greg Cravens, and reproduced here with his permission.

March 2018 Boris Matthews, PhD, LCSW